By: Dr. Conrad Gottfredson

Note: This blog is the second in a series of articles looking

at traditional Instructional Systems Design (ISD) practices through the lens of

a “performance-first” mindset. Click here to access the introductory blog to

this series: “Methodology Matters: A Performance-Based Instructional Design

Methodology”.

In 1978, I took my first graduate-level course in Instructional Systems Design. At the time, I was an Undergraduate Research Trainee (URT) for the department of Instructional Science. The first lesson in that course taught me how to write measurable learning objectives. Our textbook was titled Preparing Instructional Objectives: A Critical Tool in the Development of Effective Instruction (written by Robert Mager). For the next six years, I wrote hundreds of Mager-perfect objectives. I was a true believer. But after graduate school, when I awakened to the realities of workplace learning, things changed. As I looked at learning objectives through a “performance-first” lens, I recognized that I needed to rethink their role.

Fast forward to more current times, when our team was asked to help an organization restructure a key course to meet the requirements of all 5 Moments of Need. It was a traditional 5-day course with over a thousand slides and 270 traditional learning objectives. Focused on safety, this course had the overall performance requirement of enabling participants with the skills they needed to safely secure information, facilities, and people.

The first thing we did was conduct a Rapid Workflow Analysis (RWA). We identified 56 job tasks that participants needed to perform in their security roles and the 51 supporting knowledge topics they needed to understand as they performed the various steps within those 56 tasks.

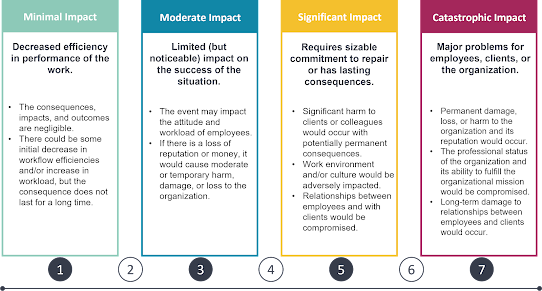

We also conducted a Critical Impact of Failure Analysis with key stakeholders to rate every task and knowledge topic using a modified version of the following rubric:

- More than 80% of the learning objectives were focused on knowledge rather than performance. Only 52 of the 270 learning objectives related directly to actual job tasks.

- Significant workflow performance areas were missed. The existing 52 performance-focused learning objectives addressed only 30% of the job tasks we identified through the RWA.

- There was a significant imbalance of learning objectives for knowledge topics. Although the remaining 218 objectives only missed 15% of the 51 supporting knowledge topics, objectives were micro-focused and contributed to cognitive overload: 20% of them included 10 to 25 learning objectives per concept.

- The most significant indictment of the course design was that 70% of the high-risk job tasks (where the critical impact of failure was significant to catastrophic) had been missed entirely (one of which included the potential for loss of life).

- Lastly, we determined that 40% of the 270 learning objectives could be met exclusively within the workflow – as people worked – rather than during the 5-day course.

|

Procedural Workflow Tasks |

Principle-Based Workflow Tasks |

|

Contact the injured or ill

employee. |

Establish performance

expectations. |

|

Arrange for a case

management meeting. |

Align employees’ goals. |

|

Hold a meeting. |

Develop employees’ job

descriptions. |

|

Engage in and communicate

about your treatment plan. |

Set company expectations. |

|

Document ongoing management

in the employee health record. |

Set educational goals. |

|

Maintain connection with an

employee off work (manager/supervisor). |

Conduct one-on-one meetings. |

|

Gather case information

from the manager/supervisor. |

Conduct annual performance

appraisals. |

|

Request medical documentation. |

Discuss employees’ impact

on workplace and culture. |

|

Provide medical documentation. |

Provide quarterly goals

updates. |

|

Receive medical documentation. |

Conduct department meetings. |

|

Send reports. |

Promote learning. |

|

Report injury, illness,

and/or challenges for remaining at work. |

Provide support and

resources. |

|

Conduct a triage assessment. |

Monitor employees’ progress. |

|

Determine the appropriate

EDMP stream. |

Assign mentorship

opportunities. |

|

Enroll an employee. |

Review comparative reports. |

|

Make a triage report. |

Plan job shadowing

opportunities. |

|

Identify barriers to

returning to/staying at work. |

Set employee development

plans. |

|

Obtain medical assessment

and/or treatment. |

Motivate employees. |

|

Resolve wage and benefit

issues. |

Provide networking

opportunities. |

|

Assemble the case team. |

Empower employees. |

|

Refer to healthcare

services. |

Celebrate employees’

success. |

A critical initial step in a performance-first approach to

instructional design is to identify the job tasks that a work team needs to

perform in their flow of work; then, organize those tasks into workflow

processes that represent how the work is done. It is at this job task level

that the work is performed. These tasks should become the performance targets

we adopt in the solutions we develop.

Effective Performance Must be Supported by Knowledge

A performance-first approach doesn’t ignore the acquisition of knowledge. Knowledge and experience are fundamental to effective performance in the flow of work. We know that knowledge is best retained and retrieved when it is anchored to specific areas of performance (e.g., job tasks). And in a performance-first approach, a specific skill is the combination of a job task with its supporting knowledge.

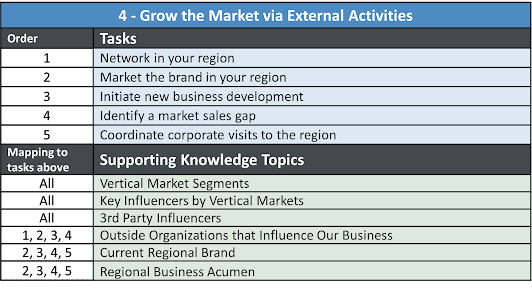

The following example is excerpted from a Learning Experience and Performance (LEaP) plan. It shows a set of skills that regional sales directors need to grow their markets via external activities. The supporting knowledge topics are mapped to each of the tasks. For example, the skill of “network in your region” requires performers to complete the steps of the first task with an understanding of the first four supporting knowledge topics in the lower half of the table.

The point here is that although a performance-first approach

focuses on the ability of a work team to successfully perform job tasks, effective

performance also requires each task to be performed with an understanding of

the key knowledge that supports it.

Real Learning Requires Experience

The learning solutions we create (synchronous or asynchronous) – whether eLearning, virtual learning, micro-learning, instructor-led or any other type of learning – represent just the beginning of the learning process. Real learning occurs in the flow of work, over time, where experience is developed. Expertise requires experience. When I had my heart valve replaced, I wasn’t concerned about the classes my surgical team members had taken. I wanted to know about their experience: how many surgeries they had done and their success rates.

Ask yourself, “Do learning objectives that are written upfront (to guide the design and development of the solutions we create and implement) truly address the continuous development of experience in the flow of work? Do they naturally lead us to skill development that is task-based and reinforced with supporting knowledge? Do they ensure that we address the full range of performance requirements?”

It is our responsibility to constantly challenge our traditions against the backdrop of the here and now. I know this blog is questioning an area of instructional design that is a long-standing and deeply held practice. Please know that my intention here has been to provide a view for you to consider. We have found what we believe is a better, faster, and more reliable way: Rapid Workflow Analysis (RWA). It provides us a prioritized view of the job tasks and related supporting knowledge that work teams need to do and understand to perform effectively. More to come on this RWA process in another blog.

Copyright © 2022 by APPLY Synergies, LLC

All Rights Reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.